Peak Health home > Plants > Coast Redwood Forests

Why Was This Indicator Chosen?

Coast redwoods are the definition of resiliency. Among the tallest trees in the world, individual redwoods may live as long as 2,000 years. Thick bark and an ability to resprout enables established adult trees to survive most wildfires, high levels of tannins make them resistant to insect and fungal infestations, and acidic soil conditions, thick duff layers, and dense shade also make coast redwood forests relatively resistant to non-native plant invasions.

Mt. Tam’s coast redwood forests provide important habitat for a number of mammals and birds, including the state and federally threatened Northern Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis caurina). Endangered coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) and threatened steelhead trout (O. mykiss) also live in the Redwood Creek Watershed on Mt. Tam.

Redwood forest communities are also good indicators of forest management practices, wildfire regimes, disease processes, and climate change. Coast redwood trees sprout prolifically from stumps, and many of Mt. Tam’s second-growth stands have higher redwood tree densities than old-growth areas as a result of turn of the century logging (Noss, 2000). High densities of tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) in second-growth redwood stands in some areas reflects a history of logging, followed by fire suppression and a lack of management actions designed to favor redwood recruitment.

Wide-spread tanoak die-back and resprouting as a result of Sudden Oak Death (SOD) has led to a persistent thicket of tanoak shoots in the redwood understory. The continual re-infection of these tanoaks prevents the shoots from developing into midstory level trees, and has reduced the habitat complexity of the mountain's redwood forests.

Finally, redwoods may serve as an indicator of climate change, particularly changes in precipitation patterns and summer fog (Micheli et al., 2016). A sudden decline in such a long-lived and resilient species would signify changes on a scale likely to be detrimental to other vegetation communities on Mt. Tam.

What is Healthy?

The desired condition for old-growth redwood forests is a complex species composition and multi-aged, multi-storied stands; coarse woody debris; tree cavities; and other nesting structures such as large limbs.

In second-growth forests, the desired condition is evidence that a stand is on a trajectory toward developing old-growth characteristics. This includes a reduction in the total stem density (trees per unit area) over time as well as the development of large-diameter trees and a multi-storied stand structure (Lorimer et al., 2009). Maintaining the existing extent of redwood forests in the One Tam area of focus is considered highly desirable because of their habitat value for Northern Spotted Owls and coho salmon, their ability to store carbon and other greenhouse gases (Cobb et al., 2017), and their iconic value.

What Are the Biggest Threats?

- The death of tanoaks, an important part of the coast redwood forest structure, from Sudden Oak Death.

- Warming temperatures, and changes to fog and precipitation patterns as a result of climate change.

- Invasive, non-native species such as panic veldtgrass (Ehrharta erecta), which are able to persist in the shady redwood understory.

- Soil compaction from recreational use of redwood forests both on and off trails.

- Legacy of logging in the region.

- Fire suppression and absence of cultural burning have resulted in a buildup of fuels, particularly in second-growth stands. This has affected forest structure and diversity as well as decreased the redwood’s wildfire resilience.

What is The Current Condition?

Old-growth redwood forests are in Good condition while second-growth areas are in Fair condition. Because the vast majority of the redwood forests on Mt. Tam are second-growth, the overall trend is Fair. The mountain's second-growth stands lack the complex structure of old-growth areas, primarily as a result of the effects of SOD.

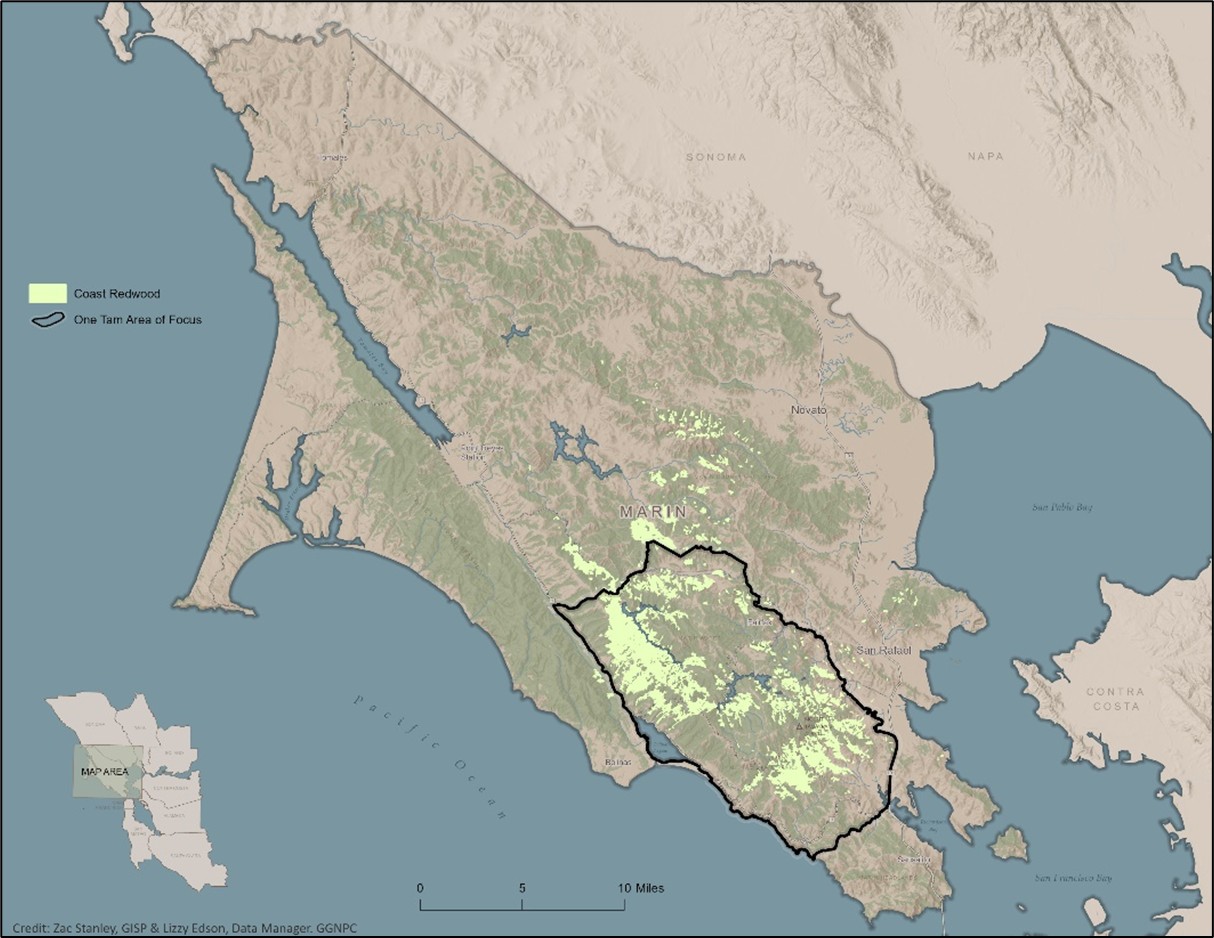

Iconic coast redwood forests (Sequoia sempervirens) are experiencing changes due to Sudden Oak Death (SOD), climate change and invasion by non-native species. The One Tam area of focus has a small amount of old-growth coast redwoods, but the majority are second-growth, having been logged at some point in the past. We have observed no detectable change in redwood forest health in the One Tam area of focus since our first assessment in 2016, and the impact of SOD on the tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) midstory appears to be slowing. Thanks to the 2018 Marin Countywide Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021), we now have a complete picture of where redwood stands are found throughout the county, as well as a suite of data that will allow us to assess coast redwood forest health and inform forest management into the future.

What is the Current Trend?

The trend for old-growth redwood forests is Improving, but second-growth redwood stands are Declining, again, primarily as a result of SOD.

How Sure Are We?

We have Moderate confidence in our assessments overall. For assessing old-growth structure, we are now looking at old-growth stands beyond Muir Woods and new second-growth beyond Marin Water lands, so more fieldwork is needed. For mid-canopy structure, we had high confidence in 2016 but no new data in 2022 so we assessed this indirectly with moderate confidence. For weed cover, confidence is high: target weed species mapping efforts have increased, with multiple surveys per year in some priority areas. Since 2016, the One Tam Conservation Management Team has invested in improving weed data collection protocols and data management systems, giving us increased confidence in this metric for this update.

What is This Assessment Based On?

- National Park Service 1994 vegetation map (Schirokauer et al., 2003)

- Marin Water vegetation maps from 2004, 2009, and 2014 (AIS, 2015)

- Marin Water broom mapping from 2003, 2010, and 2013 (unpublished data)

- Marin Water 2014 photo interpretation of SOD affected forest stands (AIS, 2015)

- Marin County Parks 2008 vegetation map (AIS, 2008)

- One Tam early detection and invasive plant mapping (Calflora, 2016, 2022)

- Larry Fox and Joe Saltenberger old-growth redwood data (Fox & Saltenberger, 2011)

- 2018 Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021)

What Don’t We Know?

Key information gaps include:

- Quantification of complex/Old-growth habitat structure including measuring and mapping coarse woody debris, tree cavities, and nesting platforms.

- Additional fieldwork is needed to connect 2018 Fine Scale Vegetation Map data (e.g., structural classifications) to on-the-ground conditions for both old-growth and second growth stands.

- A logging history study from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century would inform land managers and others of past logging operations and their continuing legacy on the landscape.

resources

Ackerly, D., Jones, A., Stacey, M., & Riordan, B. (2018). San Francisco Bay Area summary report: California’s fourth climate change assessment (Publication no. CCCA4-SUM-2018-005). State of California. https://tinyurl.com/3pc6maen

Ackerly, D. D., Cornwell, W. K., Weiss, S. B., Flint, L. E., & Flint, A. L. (2015). A geographic mosaic of climate change impacts on terrestrial vegetation: Which areas are most at risk? PloS One, 10(6), e0130629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130629

Aerial Information Systems [AIS]. (2008). Marin County Open Space District vegetation photo interpretation and mapping classification report. Prepared for Marin County Parks.

Aerial Information Systems [AIS]. (2015). Summary report for the 2014 photo interpretation and floristic reclassification of Mt. Tamalpais watershed forest and woodlands project. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District.

Brown, P. M., & Baxter, W. T. (2003). Fire history in coast redwood forests of the Mendocino Coast, California. Northwest Science, 77(2), 147–158. https://hdl.handle.net/2376/806

Buck-Diaz, J., Sikes, K., & Evens, J. M. (2021). Vegetation classification of alliances and associations in Marin County, California. Prepared for the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://tukmangeospatial.egnyte.com/dl/EBJI4cQOkH

Calflora: Information on California Plants for Education, Research, and Conservation. (2016). Website. Accessed September 2016, March 2022. http://www.calflora.org/

Cobb, R. C., Hartsough, P., Ross, N., Klein, J., LaFever, D. H., Frankel, S. J., & Rizzo, D. M. (2017). Resiliency or restoration: Management of sudden oak death before and after outbreak. Forest Phytophthoras, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5399/osu/fp.7.1.4021

Cunliffe, N. J., Cobb, R. C., Meentemeyer, R. K., Rizzo, D. M., & Gilligan, C. A. (2016). Modeling when, where, and how to manage a forest epidemic, motivated by sudden oak death in California. PNAS, 113(20), 5640–5645. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602153113

Dawson, A. (2022). Marin County wildfire history mapping project [Report]. Prepared for Marin Forest Health Project.

Dawson, T. E. (1998). Fog in the California redwood forest: Ecosystem inputs and use by plants. Oecologia, 117, 476–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050683

Farjon, A. & Schmid, R. (2013). Sequoia sempervirens. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2013: e.T34051A2841558 [Biological database]. Accessed October 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T34051A2841558.en

Fernández, M., Hamilton, H. H., & Kueppers, L. M. (2015). Back to the future: Using historical climate variation to project near-term shifts in habitat suitable for coast redwood. Global Change Biology, 21(11), 4141–4152. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13027

Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., & Holling, C. S. (2004). Regime shifts, resilience, and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 557-581. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.021103.105711

Forrestel, A. B., Ramage, B. S., Moody, T., Moritz, M. A., & Stephens, S. L. (2015). Disease, fuels and potential fire behavior: Impacts of sudden oak death in two coastal California forest types. Forest Ecology and Management, 348, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.03.024

Fox, L., III. (1989). A classification, map and volume estimate for the coast redwood forest in California (Final report; Interagency agreement no. 8CA52849). California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

Fox, L., & Saltenberger, J. (2011). Old-growth redwoods, Marin Public Lands [GIS data set]. Save-the Redwoods League.

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC]. (2023). Marin regional forest health strategy. Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://www.onetam.org/our-work/forest-health-resiliency

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC], Tukman Geospatial, & Aerial Information Systems. (2021). 2018 Marin County fine scale vegetation map datasheet. Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://tukmangeospatial.egnyte.com/dl/uQhGjac1zw

Johnstone, J. A., & Dawson, T. E. (2010). Climatic context and ecological implications of summer fog decline in the coast redwood region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(10), 4533–4538. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0915062107

Limm, E. B., Simonin, K. A., Bothman, A. G., & Dawson, T. E. (2009). Foliar water uptake: A common water acquisition strategy for plants of the redwood forest. Oecologia, 161(3), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1400-3

Lorimer, C. G., Porter, D. J., Madej, M. A., Stuart, J. D., Veirs, S. D., Norman, S. P., O’Hara, K. L., & Libby, W. J. (2009). Presettlement and modern disturbance regimes in coast redwood forests: Implications for the conservation of old-growth stands. Forest Ecology and Management, 258, 1038–1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.07.008

Maloney, P. E., Lynch, S. C., Kane, S. F., Jensen, C. E., & Rizzo, D. M. (2005). Establishment of an emerging generalist pathogen in redwood forest communities. Journal of Ecology, 93(5), 899–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01031.x

McPherson, B. A., Mori, S. R., Wood, D. L., Kelly, M., Storer, A. J., Svihra, P., & Standiford, R. B. (2010). Responses of oaks and tanoaks to the sudden oak death pathogen after 8 y of monitoring in two coastal California forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 259(12), 2248–2255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.02.020

Metz, M. R., Varner, J. M., Frangioso, K. M., Meentemeyer, R. K., & Rizzo, D. M. (2013). Unexpected redwood mortality from synergies between wildfire and an emerging infectious disease. Ecology, 94(10), 2152–2159. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0915.1

Micheli, E., Flint, L., Veloz, S., Johnson (Higgason), K., & Heller, N. (2016). Climate ready North Bay vulnerability assessment data products 1: North Bay region summary [Technical memorandum]. Prepared for California Coastal Conservancy and Regional Climate Protection Authority. https://tinyurl.com/ye2aft65

National Park Service [NPS]. (2019). Natural resource condition assessment: Golden Gate National Recreation Area (Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2019/2031). https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2267033

Noss, R. F. (Ed.). (2000). The redwood forest: History, ecology and conservation of the coast redwood. Island Press.

Parker, T. (1990). Vegetation of the Mt. Tamalpais watershed of the Marin Municipal Water District and those on the adjacent land of the Marin County Open Space [Unpublished].

Quiroga, G. B., Simler-Williams, A. B., Frangioso, K. M., Frankel, S. J., Rizzo, D. M., & Cobb, R. C. (2023). An experimental comparison of stand management approaches to sudden oak death: Prevention vs restoration [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Ramage, B. S., Forrestel, A., Moritz, M., & O’Hara, K. (2012). Sudden oak death disease progression across two forest types and spatial scales. Journal of Vegetation Science, 23(1), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01340.x

Ramage, B. S., & O’Hara, K. L. (2010). Sudden oak death-induced tanoak mortality in coast redwood forests: Current and predicted impacts to stand structure. Forests, 1(3), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01340.x

Ramage, B. S., O’Hara, K. L., & Forrestel, A. B. (2011). Forest transformation resulting from an exotic pathogen: Regeneration and tanoak mortality in coast redwood stands affected by sudden oak death. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 41(4), 763–772. https://doi.org/10.1139/x11-020

Schirokauer, D., Keeler-Wolf, T., Meinke, J., & van der Leeden, P. (2003). Plant community classification and mapping project final report: Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco Water Department Watershed Lands, Mount Tamalpais, Tomales Bay, and Samuel P. Taylor State Parks. National Park Service. https://www.nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=18209

Sillett, S. C., Van Pelt, R., Carroll, A. L., Kramer, R. D., Ambrose, A. R., & Trask, D. (2015). How do tree structure and old age affect growth potential of California redwoods? Ecological Monographs, 85(2), 181–212. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-1016.1

Simler, A. B., Metz, M. R., Frangioso, K. M., Meentemeyer, R. K., & Rizzo, D. M. (2018). Novel disturbance interactions between fire and an emerging disease impact survival and growth of resprouting trees. Ecology, 99(10), 2217–2229. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2493

Steers, R. J., Spaulding, H. L., & Wrubel, E. C. (2014). Forest structure in Muir Woods National Monument: Survey of the Redwood Canyon old-growth forest (Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SFAN/NRTR—2014/878). National Park Service. http://npshistory.com/publications/muwo/nrtr-2014-878.pdf

Swiecki, T. J., & Bernhardt, E. A. (2006). A field guide to insects and diseases of California oaks (General technical report PSW-GTR-197). U.S. Forest Service. https://doi.org/10.2737/PSW-GTR-197

Tempel, D. J., Tietje, W. D., & Winslow, D. E. (2005) Vegetation and small vertebrates of oak woodlands at low and high risk for sudden oak death in San Luis Obispo County, California. Proceedings of the sudden oak death second science symposium: The state of our knowledge (General Technical Report PSW-GTR-196, pp. 211–232). U.S. Forest Service. https://tinyurl.com/49njykzt

Thorne, J. H., Choe, H., Boynton, R. M., Bjorkman, J., Albright, W., Nydick, K., Flint, A. L., Flint, L. E., & Schwartz, M. W. (2017). The impact of climate change uncertainty on California’s vegetation and adaptation management. Ecosphere, 8(12), e02021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2021

Torregrosa, A., Flint, L. E., & Flint, A. L. (2020). Hydrologic resilience from summertime fog and recharge: A case study for coho salmon recovery planning. Journal of the American Water Resources Association, 56(1), 134–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1752-1688.12811

Van Pelt, R., Sillett, S. C., Kruse, W. A., Freund, J. A., & Kramer, R. D. (2016). Emergent crowns and light-use complementarity lead to global maximum biomass and leaf area in Sequoia sempervirens forests. Forest Ecology and Management,375, 279–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.05.018

Voigt, C. (2016). Impacts of social trails around old-growth redwood trees in Redwood National and State Parks [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Humboldt State University. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/5q47rq96z

Williams, A. (2014, October 9–10). Getting swept away by broom [Poster presentation]. California Invasive Plant Council Symposium, University of California, Chico. Retrieved from https://www.cal-ipc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Poster2014_Williams.pdf