Peak Health home > Plants > Shrublands

Note: This indicator includes coastal scrub and chaparral, including serpentine chaparral.

Why Was This Indicator Chosen?

Chaparral—the most widespread and characteristic type of shrubland in California—is dominated by hard-leaved evergreen shrubs such as chamise, manzanita, and some ceanothus species. These drought-tolerant plants are adapted to the steep slopes, shallow, rocky soils, hot, dry summers, and wet winters of the Coast Ranges. On Mt. Tam, chaparral tends to occupy elevations above 400 meters, where summers are hotter and drier, winters are colder, and more precipitation falls due to uplift.

Coastal scrub is dominated by soft-leaved, woody shrubs that thrive in the narrow maritime climate zone along the California coast. These communities are typically found on well-developed soils below 400 meters, where summer fog is frequent. Coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) is characteristic of the northern division of coastal scrub (Ford & Hayes, 2007), which predominates on Mt. Tam.

The shrublands of Mt. Tam can be used as indicators of successional processes, disturbance, and habitat quality for terrestrial birds. Intact shrublands are fairly resistant to plant invasions, in part due to the high densities of small herbivores that shelter and forage in the understory (Lambrinos, 2002). The preservation of large blocks of coastal scrub and chaparral is also critical to the long-term viability of many bird species (CalPIF, 2004).

What is Healthy?

The desired condition for the One Tam area of focus is the persistence of large, weed-free blocks of shrublands vegetation that provide habitat for plant and wildlife species sensitive to fragmentation. As forested habitats have replaced shrublands in many locations over the past century of fire exclusion, preservation of shrublands acreage along forest edges has become even more desirable.

What Are the Biggest Threats?

- Invasive species: Coastal scrub is generally less dense than chaparral, making it more vulnerable, especially in gaps and along patch edges; both communities are vulnerable to invasion along roads, trails, fuel breaks, etc.

- Douglas-fir encroachment due to a lack of fire, and the resulting impacts on shade-intolerant scrub and chaparral species

- Shifts in shrubland community composition with changes in maritime temperature and precipitation as a result of climate change

- Possible impacts from Phytophthora pathogens

What is The Current Condition?

The overall condition of the shrublands on Mt. Tam is Fair. Declines in condition and trend from what we knew in 2016 (the overall condition was Good in 2016) to our best current understanding in 2022 should be viewed with the understanding that in each of the two years, we measured slightly different things in two of the metrics. However, this does not account for all of the differences in condition and trend between the two analyses. The condition of shrublands in the area of focus has been reduced from good in 2016 to caution in 2022 because new data and analyses indicate a higher level of threat and a greater loss of shrublands extent than was previously known. Numerous lines of evidence reveal that shrublands are losing acreage to forest succession due to fire suppression, and more shrubland acres than were previously known are occupied by invasive plants.

What is the Current Trend?

Overall, this community has a trend of Declining.

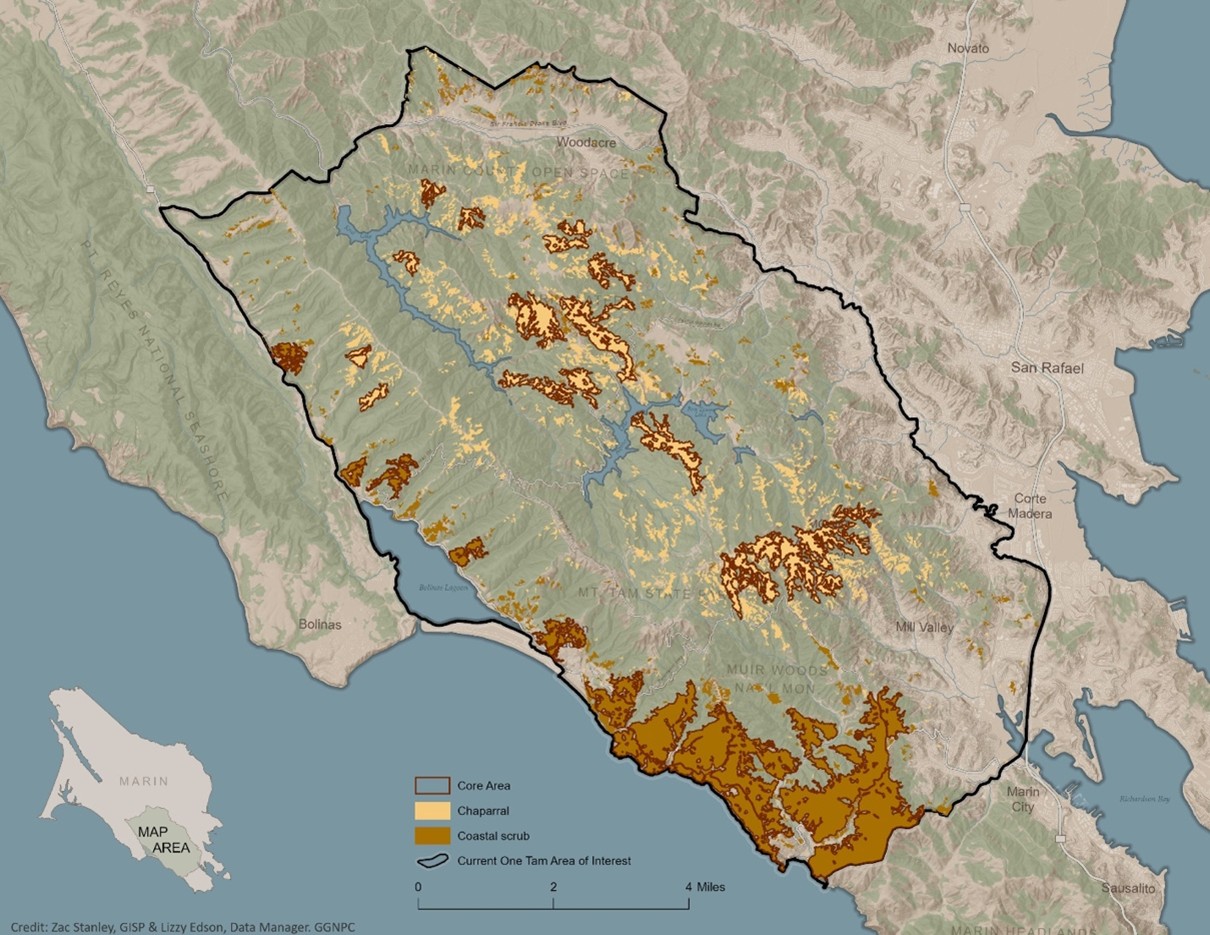

Map of core chaparral and coastal scrub locations in the One Tam area of focus

How Sure Are We?

We have Moderate confidence in this assessment. The 2018 Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021) establishes a reliable baseline for core shrublands patches, but—due to disparate time series, classifications, and mapping methodologies—does not support direct comparison with earlier vegetation maps used by the One Tam partner agencies. Quantitative and qualitative evidence indicate an ongoing trend of shrublands-to-forest succession, but time-series data that would determine the rate of change and degree of concern for the One Tam area of focus as a whole are lacking All One Tam partner agencies’ weed control and early detection programs now provide relatively comprehensive surveillance and mapping cover throughout most of the area of focus, and the countywide vegetation map and shared Calflora Weed Manager database also enable comprehensive status assessments across the area of focus. However, while our confidence in the current status of invasive plants is relatively high, our confidence in trend detection is relatively low.

What is This Assessment Based On?

- Marin Water vegetation maps (2009, 2014; GGNPC et al., 2021).

- Marin County Parks vegetation map, created with a methodology similar to that used by Marin Water (2008; Aerial Information Systems, 2008).

- National Park Service vegetation map (1994, used for National Park Service and California State Parks; Schirokauer et al., 2003).

- One Tam early detection and invasive plant mapping (Calflora, 2022).

- Marin Countywide Fine Scale Vegetation Map, 2018 (GGNPC et al., 2021).

What Don’t We Know?

Key information gaps include:

- Monitoring that captures compositional change in all communities at the landscape scale

- Time series data, including vegetation maps updated in five-year intervals to detect expansions and contraction among grasslands, oak woodlands, and shrub vegetation types

- Non-native, invasive species surveillance of off-trail areas in shrublands

- Percent tree cover

- Plant pathogen presence and distribution

resources

Ackerly, D. D., Ryals, R. A., Cornwell, W. K., Loarie, S. R., Veloz, S., Higgason, K. D., Silver, W. L., & Dawson, T. E. (2012). Potential impacts of climate change on biodiversity and ecosystem services in the San Francisco Bay Area (Publication no. CEC-500-2012-037). Prepared for California Energy Commission. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1qm749nx

Aerial Information Systems [AIS]. (2008). Marin County Open Space District vegetation photo interpretation and mapping classification report. Prepared for Marin County Parks.

Aerial Information Systems [AIS]. (2015). Summary report for the 2014 photo interpretation and floristic reclassification of Mt. Tamalpais watershed forest and woodlands project. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District.

Calflora: Information on California Plants for Education, Research, and Conservation. (2016). Website. Accessed August 2022. http://www.calflora.org/

California Partners in Flight. (2004). The coastal scrub and chaparral bird conservation plan: A strategy for protecting and managing coastal scrub and chaparral habitats and associated birds in California (Version 2.0). PRBO Conservation Science. http://www.prbo.org/calpif/pdfs/scrub.v-2.pdf

Callaway, R. M., & Davis, F. W. (1993). Vegetation dynamics, fire, and the physical environment in coastal central California. Ecology, 74(5), 1567–1578. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1940084

Chase, M. K., Holmes, A. L., Gardali, T., Ballard, G., Geupel, G. R., Geoffrey, R., & Nur, N. (2005). Two decades of change in a coastal scrub community: Songbird responses to plant succession. In C. J. Ralph & T. D. Rich (Eds.), Bird conservation implementation and integration in the Americas: Proceedings of the third international Partners in Flight conference, March 20–24, 2002. (Volume 1, Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191, pp. 613–616). U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/32012

Cornwell, W. K., Stuart, S., Ramirez, A., Dolanc, C. R., Thorne, J. H., & Ackerly, D. D. (2012). Climate change impacts on California vegetation: Physiology, life history, and ecosystem change. (Publication no. CEC-500-2012-023). Prepared for California Energy Commission. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6d21h3q8

D’Antonio, C. M. (1993). Mechanisms controlling invasion of coastal plant communities by the alien succulent Carpobrotus edulis. Ecology, 74(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939503

Dickens, S. J. M., & Allen, E. B. (2014). Exotic plant invasion alters chaparral ecosystem resistance and resilience pre- and post-wildfire. Biological Invasions, 16(5), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-013-0566-0

Ford, L. D., & Hayes, G. F. (2007). Northern coastal scrub and coastal prairie. In M. Barbour, T. Keeler-Wolf, & A. A. Schoenherr (Eds.), Terrestrial vegetation of California (3rd ed., pp. 180–207). University of California Press.

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC], Tukman Geospatial, & Aerial Information Systems. (2021). 2018 Marin County fine scale vegetation map datasheet. Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://tukmangeospatial.egnyte.com/dl/uQhGjac1zw

Heady, H. F., Foin, T. C., Hektner, M. M., Taylor, D. W., Barbour, M. G., & Barry, W. J. (1988). Coastal prairie and northern coastal scrub. In M. Barbour, T. Keeler-Wolf, & A. A. Schoenherr (Eds.), Terrestrial vegetation of California (3rd ed., pp. 733–760). University of California Press.

Horton, T. R., Bruns, T. D., & Parker, V. T. (1999). Ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Arctostaphylos contribute to Pseudotsuga menziesii establishment. Canadian Journal of Botany, 77(1), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1139/b98-208

Hsu, W., Remar, A., Williams, E., McClure, A., Kannan, S., Steers, R., Schmidt, C., & Skiles, J. W. (2012, March 19–23). The changing California coast: Relationships between climatic variables and coastal vegetation succession [Paper presentation]. ASPRS Annual Conference, Sacramento, CA. http://www.asprs.org/a/publications/proceedings/Sacramento2012/files/Hsu.pdf

Johnstone, J. A., & Dawson, T. E. (2010). Climatic context and ecological implications of summer fog decline in the coast redwood region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [PNAS], 107(10), 4533–4538. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0915062107

Keeley, J. E. (1991). Seed germination and life history syndromes in the California chaparral. Botanical Review, 57(2), 81–116. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4354163

Keeley, J. E. (2005). Fire history of the San Francisco East Bay region and implications for landscape patterns. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 14(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF05003

Keeley, J. E., & Brennan, T. J. (2012). Fire-driven alien invasion in a fire-adapted ecosystem. Oecologia,169(4), 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2253-8

Kemper, J., Cowling, R. M., & Richardson, D. M. (1999). Fragmentation of South African renosterveld shrublands: Effects on plant community structure and conservation implications. Biological Conservation, 90(2), 103–111. https://overbergrenosterveld.org.za/kemper1.pdf

Lambrinos, J. G. (2002). The variable invasive success of Cortaderia species in a complex landscape. Ecology, 83(2), 518–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/2680032

Paddock, W. A. S., III, Davis, S. D., Pratt, R. B., Jacobsen, A. L., Tobin, M. F., López-Portillo, J., & Ewers, F. W. (2013). Factors determining mortality of adult chaparral shrubs in an extreme drought year in California. Aliso, 31(1), 49–57. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol31/iss1/8

Panorama Environmental. (2019). Marin Municipal Water District biodiversity, fire, and fuels integrated plan. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District. https://tinyurl.com/2z9nxu2w

Sawyer, J. O., Keeler-Wolf, T., & Evens, J. (2009). Manual of California vegetation. California Native Plant Society Press.

Schirokauer, D., Keeler-Wolf, T., Meinke, J., & van der Leeden, P. (2003). Plant community classification and mapping project: Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and the surrounding wildlands (Final report). National Park Service.

Startin, C. R. (2022). Assessing woody plant encroachment in Marin County, California, 1952–2018 [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Southern California. https://tinyurl.com/yck77dt7

Thorne, J. H., Choe, H., Boynton, R. M., Bjorkman, J., Albright, W., Nydick, K., Flint, A. L., Flint, L. E., & Schwartz, M. W. (2017). The impact of climate change uncertainty on California’s vegetation and adaptation management. Ecosphere, 8(12), e02021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2021

Williams, A. (2014, October 8–11). Getting swept away by broom [Poster presentation]. California Invasive Plant Council Symposium. University of California, Chico. https://www.cal-ipc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Poster2014_Williams.pdf

Zedler, P. H. (1995). Fire frequency in southern California shrublands: Biological effects and management options. In J. E. Keeley & T. Scott (Eds.), Brushfires in California wildlands: Ecology and resource management (pp. 101–112). International Association of Wildland Fire.