Peak Health home > Plants > Oak Woodlands

Why Was This Indicator Chosen?

Open-canopy oak woodlands on Mt. Tam are characterized by the presence of long-lived acorn-producing trees from the genus Quercus. Although open-canopy oak woodlands have many tree species in common with mixed hardwood forests, the lower density and patchier distribution of trees create a distinct habitat structure for both herbaceous plants and wildlife. Understory species also include a distinct and more varied array of grasses, sedges, and forbs than closed-canopy forests (Evans & Kentner, 2006).

Oak woodlands in California support 1,400 species of flowering plants and over 300 species of vertebrates—more species than any other habitat type in the state (Mayer et al., 1986). On Mt. Tam, open-canopy oak woodlands can be used as an indicator of forest disease, fire regimes, and habitat quality for a number of oak-dependent birds (Rizzo et al., 2003; Holmes et al., 2008; Cocking, 2014). Lace lichen (Ramalina menziesii), which is California’s state lichen, primarily grows in open-canopy oak woodlands and is a good indicator of air quality (Sharnoff, 2014).

What is Healthy?

The maintenance of the full spatial extent of this vegetation type, the persistence of a discontinuous canopy dominated by trees from the genus Quercus, and discontinuous shrub and herbaceous layers dominated by native species.

Good examples of this type can be found in the Bon Tempe/Lake Lagunitas area and in the Cascade Canyon Preserve.

What Are the Biggest Threats?

- More than 90 percent of open-canopy oak woodlands on Marin Water lands is impacted by Sudden Oak Death (SOD) (AIS, 2015)

- A loss of fire to maintain an open canopy structure, limit the development of a shrub layer, and prevent the establishment of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and reduce the build-up of fuels and the risk of high-intensity wildfires with the potential to kill mature oaks

- High densities of deer browsing pressure on broadleaf tree seedlings and young saplings, leading to a depressed rate of new tree recruitment (Beschta, 2005; Ripple & Beschta, 2008)

- Acorn predation by introduced wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo)

- Impacts from invasive species such as French broom (Genista monspessulana) and non-native grasses which can reduce habitat function and biodiversity

- Fire suppression on Mt. Tam has shifted some areas from oak woodland to Douglas-fir conifer forest, changed oak woodland stand structure, and increased fuel loads.

What is the Current Condition?

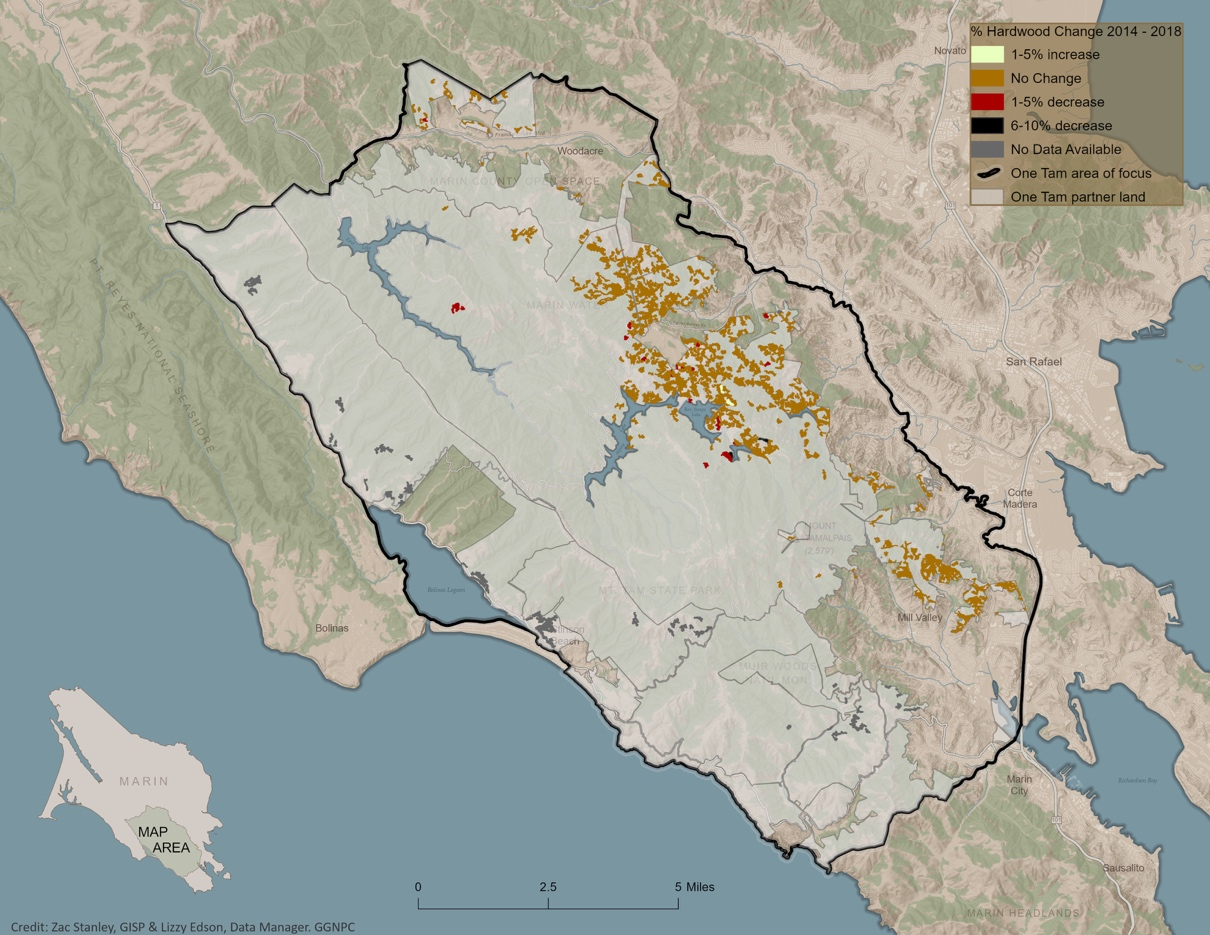

Open-canopy oak woodlands on Mt. Tam are in Fair condition overall. The 2018 Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021a) shows that there are 1,594 acres of oak woodlands in the area of focus, 99% of which have at least 25% hardwood cover. Only nine acres fall below the 25% threshold, indicating that the condition of hardwood cover is good. However, 73% of oak woodlands have hardwood cover greater than 60%, leaving just 418 acres of what we consider to be open-canopy woodlands. When compared to closed-canopy hardwood forests, the open-canopy acres are even fewer (just under 370) when the additional canopy cover of conifers in these stands is taken into consideration. In addition, non-native, invasive species remain a significant concern.

The 2018 Marin Countywide Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021a) is the product of Marin County’s first simultaneous, multi-agency vegetation mapping effort to use a single consistent methodology across multiple jurisdictions. The quality and consistency of these data make the new map a foundational resource for calculating current baseline acreages of open-canopy oak woodlands in the One Tam area of focus. Looking ahead, future comparisons against the 2018 Fine Scale Vegetation Map should have greater accuracy and confidence levels.

What is the Current Trend?

Overall, these communities are Declining, primarily as a result of SOD and invasive species.

How Sure Are We?

Changes in mapping techniques and comparison areas reduce our general confidence in trend determination. However, we have relatively high confidence in the quality of mortality and hardwood-cover data and the level at which these are represented on all One Tam partner agency lands in the area of focus. This new dataset covers 100% of Mt. Tam’s oak woodlands when measuring 2018 mortality and hardwood-cover attributes, and 90% of oak woodlands when measuring hardwood decline from 2014 to 2018. We therefore have moderate confidence in comparing the results from the two assessment periods (2016 and 2022).

What is This Assessment Based On?

Aerial Surveys and Mapping:

- Standardized 2004–2014 County Parks/Marin Water vegetation map (GGNPC et al., 2021b)

- 2018 Marin County Fine Scale Vegetation Map (GGNPC et al., 2021a)

- Marin Water broom mapping from 2010 draft vegmgmt_polys_9_3, and 2013 and 2018 broom remapping

- Marin Water 2015 photo interpretation of SOD-affected forest stands (AIS, 2015)

- Marin Water, Marin County Parks, California State Parks, and National Park Service weed records from both the Calflora database and internal records

What Don’t We Know?

Key information gaps include:

- A measure of the diversity of native species so that we can try to maintain species richness at the reference condition for this community type

- Data on the age structure of native trees to determine if new trees are being recruited at a rate that is sufficient to maintain the total acres and structural integrity of open-canopy oak woodlands over time

- Greater understanding of the habitat function and value of open- vs. closed-canopy oak woodlands

resources

Aerial Information Systems, Inc. [AIS]. (2015). Summary report for the 2014 photo interpretation and floristic reclassification of Mt. Tamalpais watershed forest and woodlands project. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District.

Allen-Diaz, B., Standiford, R., & Jackson, R. D. (2007). Oak woodlands and forests. In M. G. Barbour, T. Keeler-Wolf, & A. A. Schoenherr (Eds.), Terrestrial vegetation of California (3rd ed., pp. 313–335). University of California Press. https://nature.berkeley.edu/~standifo/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Terrestrial-Vegetation-Oak-Chapter.pdf

Bay Area Open Space Council [BAOSC]. 2011. The conservation lands network 1.0: San Francisco Bay Area upland habitat goals project report. https://www.bayarealands.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CLN-1.0-Progress-Report.pdf

Bay Area Open Space Council [BAOSC]. (2019a). The conservation lands network 2.0 [Report]. https://www.bayarealands.org/maps-data

Bay Area Open Space Council [BAOSC]. (2019b). Appendix B: Coarse filter conservation targets. In The conservation lands network 2.0 [Report]. https://www.bayarealands.org/maps-data

Bernhardt, E. A., & Swiecki, T. J. (2001). Restoring oak woodlands in California: Theory and practice. Phytosphere Research. http://phytosphere.com/restoringoakwoodlands/oakrestoration.htm

Beschta, R. L. (2005). Reduced cottonwood recruitment following extirpation of wolves in Yellowstone's Northern Range. Ecology, 86(2), 391–403. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3450960

Calflora: Information on California Plants for Education, Research, and Conservation. (2016). Accessed September 2016, March 2022. http://www.calflora.org

California Department of Fish and Wildlife [CDFW]. (2023). California Sensitive Natural Communities. Accessed December 2023. https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=153609&inline

California Native Plant Society [CNPS]. (2022). A manual of California vegetation [Online]. Retrieved December 19, 2022. http://www.cnps.org/cnps/vegetation

California Natural Resources Agency [CNRA]. (2021). Conserved areas explorer [Data set]. Updated May 18, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023. https://www.californianature.ca.gov/apps/conserved-areas-explorer/explore

Chitambar, J. C. (2016, June 21). California pest rating for Phytophthora quercina T. Jung 1999. Pest rating proposals and final ratings. California Department of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved November 1, 2023. https://blogs.cdfa.ca.gov/Section3162/?p=2148

Cocking, M. I., Varner, J. M., & Engber, E. A. (2015). Conifer encroachment in California oak woodlands. In R. B. Standiford & K. Purcell (Eds.), Proceedings of the seventh California oak symposium: Managing oak woodlands in a dynamic world (General technical report PSW-GTR-251). U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/50018

Cunniffe, N. J., Cobb, R. C., Meentemeyer, R. K., Rizzo, D. M., & Gilligan, C. A. (2016). Modeling when, where, and how to manage a forest epidemic, motivated by sudden oak death in California. PNAS, 113(20), 5640–5645. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602153113

Davis, F. W., Tyler, C. M., & Mahall, B. E. (2011). Consumer control of oak demography in a Mediterranean-climate savanna. Ecosphere, 2(10), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES11-00187.1

Edson, E., Farrell, S., Fish, A., Gardali, T., Klein, J., Kuhn, W., Merkle, W., O’Herron, M., & Williams, A. (Eds.). (2016). Measuring the health of a mountain: A report on Mount Tamalpais’ natural resources. https://www.onetam.org/media/pdfs/peak-health-white-paper-2016.pdf

Evens, J., Kentner, E., & Klein, J. (2006). Classification of vegetation associations from the Mount Tamalpais watershed, Nicasio reservoir, and Soulajule reservoir in Marin County, California [Technical report]. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328432434

Garrison, B. A., Otahal, C. D., & Triggs, M. L. (2002). Age structure and growth of California black oak (Quercus kelloggii) in the Central Sierra Nevada, California (General technical report PSW-GTR-184). U.S. Forest Service. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15109174

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC]. (2023). Marin regional forest health strategy. Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://www.onetam.org/our-work/forest-health-resiliency

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC], Tukman Geospatial, & Aerial Information Systems. (2021a). 2018 Marin County fine scale vegetation map datasheet. Tamalpais Lands Collaborative (One Tam). https://tukmangeospatial.egnyte.com/dl/uQhGjac1zw

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy [GGNPC], Tukman Geospatial, & Aerial Information Systems. (2021b). Standardized 2004–2014 county parks/Marin Water vegetation map [Data set]. Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. https://vegmap.press/marin_standardized_04_14_datasheet

Holmes, K. A., Veblen, K. E., Young, T. P., & Berry, A. M. (2008). California oaks and fire: A review and case study (General technical report PSW-GTR-217). U.S. Forest Service. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254476855_California_Oaks_and_Fire_A_Review_and_Case_Study

iNaturalist Community. (2023). California oakwatch. iNaturalist. https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/california-oakwatch

Kozanitas, M., Metz, M. R., Osmundson, T. W., Serrano, M. S., & Garbelotto, M. (2022). The epidemiology of sudden oak death disease caused by Phytophthora ramorum in a mixed bay laurel-oak woodland provides important clues for disease management. Pathogens, 11(2), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11020250

Kuhn, B. A. (2010). Road systems, land use, and related patterns of valley oak (Quercus lobata Nee) populations, seedling recruitment, and herbivory [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara]. ProQuest. https://www.proquest.com/docview/757903319

Marin Municipal Water District. (2022). Vegetation management report: Fiscal year 2022. https://tinyurl.com/mtkshysv

May & Associates, Inc. (2015). Vegetation and biodiversity management plan. Prepared for Marin County Parks/Marin Open Space District. guidingdocuments_vbmp2015.pdf (marincounty.org)

National Centers for Environmental Information [NCEI]. (2023). Climate at a glance: County time series. Retrieved October 26, 2023. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/climate-at-a-glance/county/time-series

Panorama Environmental, Inc. (2019). Marin Municipal Water District biodiversity, fire, and fuels integrated plan. Prepared for Marin Municipal Water District. https://tinyurl.com/2z9nxu2w

Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R.L. (2007). Hardwood tree decline following large carnivore loss on the Great Plains, USA. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 5(5), 241–246. https://tinyurl.com/2cfh8taj

Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R. L. (2008). Trophic cascades involving cougar, mule deer, and black oaks in Yosemite National Park. Biological Conservation, 141(5), 1249–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.02.028

Rizzo, D. M., & Garbelotto, M. (2003). Sudden oak death: Endangering California and Oregon forest ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 1(5), 197–204. https://nature.berkeley.edu/garbelotto/downloads/rizzo2003.pdf

Sawyer, J. O., Keeler-Wolf, T., & Evens, J. (2009). A manual of California vegetation (2nd ed.). California Native Plant Society.

Schirokauer, D., Keeler-Wolf, T., Menke, J., & van der Leeden, P. (2003). Plant community classification and mapping project final report: Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco Water Department Watershed Lands, Mount Tamalpais, Tomales Bay, and Samuel P. Taylor State Parks. National Park Service. https://www.nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=18209

Sharnoff, S. (2014). A field guide to California lichens. Yale University Press.

Sullivan, T. J., McDonnell, T. C., McPherson, G. T., Mackey, S. D., & Moore, D. (2011). Evaluation of the sensitivity of inventory and monitoring national parks to nutrient enrichment effects from atmospheric nitrogen deposition: San Francisco Bay Area Network (SFAN) (Natural resource report NPS/NRPC/ARD/NRR—2011/325). National Park Service. https://permanent.fdlp.gov/gpo135921/sfan_n_sensitivity_2011-02.pdf

Thorne, J. H., Boynton, R. M., Holguin, A. J., Stewart, J. A., & Bjorkman, J. (2016). A climate change vulnerability assessment of California’s terrestrial vegetation. California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Sacramento, CA. https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=116208&inline

Thorne, J. H., Choe, H., Boynton, R. M., Bjorkman, J., Albright, W., Nydick, K., Flint, A. L., Flint, L. E., & Schwartz, M. W. (2017). The impact of climate uncertainty on California’s vegetation and adaptation management. Ecosphere, 8(12), e02021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2021

Tyler, C., Kuhn, B., & Davis, F. (2006). Demography and recruitment limitations of three oak species in California. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 81(12), 127–152. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/506025

Tyler, C. M., Mahall, B. E., Davis, F. W., & Hall, M. (2002). Factors limiting recruitment in valley and coast live oak. Proceedings of the fifth symposium on oak woodlands: Oaks in California's changing landscape (General technical report PSW-GTR-184). U.S. Forest Service. http://danr.ucop.edu/ihrmp/proceed/symproc50.html

University of California Cooperative Extension [UCCE]. (2017). Goldspotted oak borer (Forest insect and disease leaflet 183). U.S. Forest Service. https://ucanr.edu/sites/gsobinfo